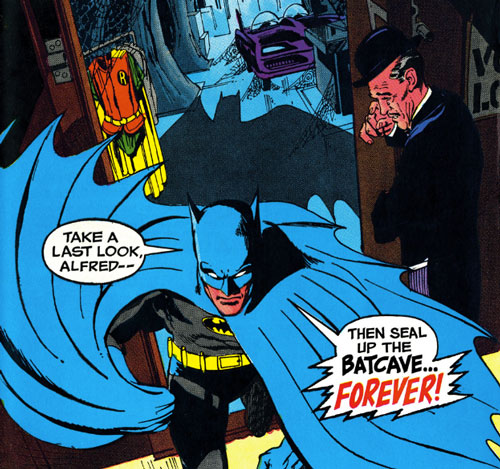

Tim, Paul and Ian--great show. I've always loved the late 60s transition from the more "pop" Batman comic stories took a very serious turn with the Irv Novick / Frank Robbins period. It was gradual, not an overnight thing beginning with the

"One Bullet Too Many" story, but a shift fans took notice of long before that final Bat-issue of the decade. Above all else, the original Batman was back and started to stand out among the DC superheroes as something more than just another cape or a character from a TV series.

If you don't mind, I would like to re-post my 4/28/18 observation about this period of the Bat-comics , and what some fans were thinking at the time:

BATWINGED HORNET wrote: ↑Sat Apr 28, 2018 2:10 pm

One thing I wish some historians would acknowledge is how DC's flirtation with the tone of the TV series was short lived; even as

Batman entered its third season, the comic took a well-received turn back to some darker storylines in the hands of writer Frank Robbins and artist Irv Novick, all before the Adams/O'Neil period. For example, take a look at the kind of subjects covered in

Batman #204 (August, 1968) and #206 (November, 1968)--

That's a far cry from Louie, Dr. Cassandra, surfing, Catwoman trying to be the queen of fashion and Londinium.

Weldon's history is interesting, and shines a light on comic fans not appreciating the '66 series take on the character while it was on ABC.

Of note is the reference to some fans feeling TV Robin was "too much" (I assume they meant the "holy-isms" more than anything else), which was echoed in the letters pages of Batman comics of the period, along with how much the readers supported the comic

not borrowing many of the TV series' hallmarks, such as...

Onomatopoeia (

Batman #195 - September, 1967)--

Bat-gadgets (

Batman # 206 - November, 1968) --

Robin's puns (

Batman #200 - March, 1968) --

Camp (

Batman # 206 - November, 1968) --

...but the letters pages also revealed strong support for the title to return to its darker roots. For example,

Batman #199 (February, 1968) --

If some of the Bat-titles took a sales drop, it was worth it, as I do not believe the character would have survived if he never made the second big change of the decade (after the "New Look" in 1964) to become that serious detective dealing with situations not limited to costumed villains.

About the reason for the sales drop in the early 70s, Carmine Infantino offered the following:

"1974 had been a huge success for DC, I was the toast of the town, receiving thank yous and congratulations..."

"With rare exceptions like the superhero boom of the early 40s and the Batman boom of the mid-60s, the comic book business tends to make more money on licensing of characters for film, TV, toys, etc., than it does in publishing. If i remember correctly, we did about $800,000 in publishing alone in '74. I had brought the company up from being creamed by Marvel to being dead even with them."

He goes on to discuss the sales drop:

"The only way I could protect DC's rack space position was to go head to head with Marvel's expansion. I knew many of the new Marvel and DC would lose money, but if I didn't match their production, we would lose existing titles and be blown off the racks by the new Marvel books. The resulting loss of our share of the market would be devastating and take much longer to recoup than calling Marvel's bluff long enough for them to come to their senses and cancel the poorer-selling titles."

...and about Batman at the same time:

"It is my understanding that, the year after I left, sales were the worst in DC history. People told me that Batman had only a 12% sell-through, the lowest in the Caped Crusader's career."

--from

The Amazing World of Carmine Infantino.

Comics across the board were suffering, so I think Batman--no matter how much his titles were creatively satisfying month-to-month--was not immune to the problems smacking the industry by the mid 70s.

About the Gothic influence, look to the

Dark Shadows phenomenon for that, as the soap-opera mainstreamed Gothic horror tropes like ghosts, demons, leviathans, vampires, and other supernatural elements to a far greater degree than Hammer films, or any other productions in a way not felt (culturally speaking) since Universal's monster heyday of the 30s and 40s.

In the early 1970s alone, you would see DC have a number of covers featuring superheroes meeting ghosts, Satanic figures, even Warren magazine-like executioners:

The Flash #194, from 2/1970:

World's Finest

World's Finest #209, from 2/1972:

Wonder Woman

Wonder Woman #199, from 4/1972:

Of course, the long-running DC ghost/mystery/try-out titles such as

House of Mystery (1951-83),

House of Secrets (1956-78) and

Unexpected (1956-82) all made a big shift to outright horror by the end of the 60s, then going to add (but not limited to)

The Witching Hour (1969-78),

Ghosts (1971-82) and

Secrets of Sinister House (1972-74) to the line-up. Even some of the final issues of the original

Teen Titans comic (ending in 1973) leaned toward the supernatural.

This harder shift toward undeniably horror-based characters--like the creation of Man-Bat--was not a

"throw it against the wall and see what sticks" case, but an serious acknowledgement of the popularity of a series such as

Dark Shadows, and obviously, Warren's books like

Eerie and

Creepy.

Marvel certainly jumped on that Gothic horror / monster train with both feet with a good number titles:

Tower of Shadows (1969-70)

Chamber of Chills (1972-76)

Fear (1972-75)

Dead of Night (1973-75)

Creatures on the Loose (1971-75; formerly

Tower of Shadows)

...and that was far from the only Marvel stab at that aforementioned train.

Sign of the times and the changing tastes of comic readers.